Getting Assessment Right I

Assessment Across the Curriculum

It’s a bit of a tricky one, this.

Ever since Ofsted decided that they were bothered about the wider curriculum, it was inevitable that they’d be after us to develop assessment across the curriculum too.

For as long as I can remember, it wasn’t something that we gave much thought to. Assessment in subjects like history, geography or art and design were generally reduced to 'most/some/all' statements that lurked at the bottom of a medium-term plan.

With curriculum coming more sharply into focus however, assessment has now become a priority for lots of schools.

Three Big Questions

In getting to grips with assessment across the curriculum, there are three big questions we need to address:

-

-

- What should assessment focus on?

- How do we know that a particular pupil has mastered a concept?

- What tasks or responses would indicate this?

-

The first question sounds like a straightforward one, but it’s actually a bit more complicated than it seems.

To begin with, people quite often don’t actually agree on what the focus of assessment should be.

Dylan Wiliam, professor of assessment at the UCL Institute of Education and all round assessment guru talks about the way that assessments ‘operationalize constructs’. He explains that assessments, or the design of assessments, force us to get off the fence in terms of what we believe a subject to be about (more on this here).

For example, some people believe that ‘being good’ at history is about the recall of historical knowledge. Knowing your facts and dates.

Others believe that history is much more than this and suggest that the ability to construct historical arguments is just as important as recalling the facts and dates.

This belief – and the need to make a choice – has a direct impact on the assessments we then design.

If you’re in the first camp, then a multi-choice type assessment would give you exactly what you're after.

However, if you believe that history is more than dates and facts, then you are much more likely to go with a model where the pupils are asked to write an extended answer or essay-style response.

The important thing to remember is that there isn’t a right or wrong answer to this – we just have to decide what we mean when we talk about ‘being good’ at a subject.

And convey that decision clearly.

Pretty Much Everything

At our school, we decided for ourselves and then expressed it clearly in subject statement documents.

These documents are on our website and they all begin with a quote that sums up what each subject means to us.

Beyond each quote, they then go on to set our stall out in terms of how we view different strands of knowledge within that particular subject, along with how we assess it.

When thinking about the different subjects, we had a similar reaction in each.

We decided that history was about more than just knowing facts and dates, but we also decided that we felt the same about geography, art and design, design and technology – to be honest – pretty much everything.

This decision gave us a clear indication of what type of assessment we would need to design.

We needed something that would assess the children’s knowledge, but also their ability to apply it in context.

Say What You See

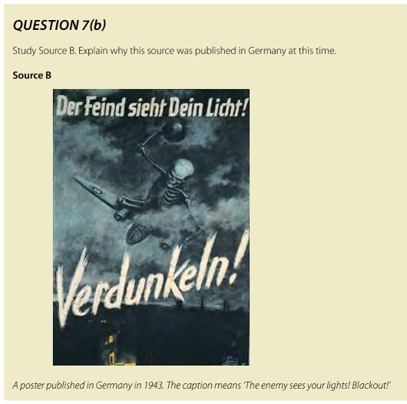

To get to grips with the second question - how we’d know that a particular pupil had mastered a concept - I had a look at examples from beyond primary.

What we wanted was a means of assessing how well the children were learning the curriculum we’d planned, and whilst summative assessments in subjects like geography, history or art and design were few and far between in primary, they did exist at the end of KS4.

GCSE exams are not perfect, but they do give us a useful glimpse into the kind of things we’re expecting children to demonstrate.

In history, for example, it was clear that the ability to analyse sources was important in identifying whether children had mastered a concept.

If we look at the GCSE mark schemes (see AQA images below), they give examples of indicative content which show that, in order to have mastered the content (i.e. responses that demonstrate pupils are operating at the top level of the mark scheme – grades 8/9), the children need to be able to do two things.

-

-

- Interpret the source. In other words to say what they see

- Expand on it. Add it to stuff that they’ve already got in their heads.

-

![]()

This seems to be a useful combination of knowledge and application, and it also helps us with the final question of what the assessment tasks might look like.

The idea of using source analysis as a summative assessment tool is supported by the work of Jan Meyer and Ray Land on threshold concepts.

Meyer and Land define threshold concepts as ‘conceptual gateways’ into more advanced ways of thinking about topics and subject areas. (There’s more on the defining features of threshold concepts here).

I’m not sure that ‘analysis’ is a threshold concept in itself – it’s probably too broad for that – but what it does represent is a particular way of thinking within a discipline.

A carefully planned source analysis task is an activity that can unlock a number of different threshold concepts within the subject, and as a result, enable us to assess how well the pupils have mastered the content.

Next Step - The Whole Curriculum

We decided that this would be the approach we’d use for assessment across the whole curriculum. After all, it’s just as important to learn how to analyse in geography as it is in history.

You can say the same about art and design or music too.

Now, we have to be a bit careful with this, after all, the ability to analyse isn’t a transferable skill. We have to learn what it looks like in different subject disciplines.

That said, if this is carefully modelled then there’s no reason why we can’t use a consistent approach for assessing most subjects.

With this in mind, we set about identifying appropriate sources within different subjects that would be used as a final summative assessment.

The intention wasn’t to find a source that unlocked all of the content covered, just as this isn’t the aim at GCSE.

What we did want was something that gave the children the opportunity to draw on multiple aspects of knowledge from their project and apply it in the context given.

We decided that this would be an unseen source – but that it would be familiar to other sources they had used during the unit.

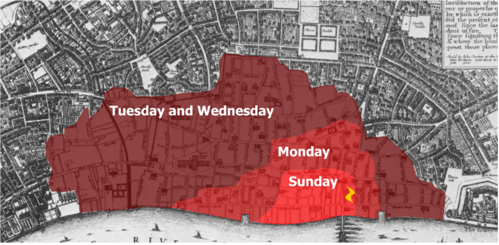

The Great Fire of London

For example, if you were studying the Great Fire of London in history, you might select a final source like this map that shows the spread of the fire over four days:

Once we’ve decided on the source we’re going to use for our assessment, we can now start to create our own indicative response – or at least begin to think about the different aspects of knowledge we are hoping the source will unlock.

To effectively analyse this source, we’d probably want the children to know the following things…

-

-

- Where the fire started

- How and why the fire spread (including weather, building type and proximity)

- What people did about it

-

Beyond this, we’d also want them familiar with maps of London and some significant landmarks (i.e. the River Thames, London Bridge, the Tower of London etc...)

Having such a clearly defined end-point in terms of assessment means that we can now work backwards to ensure that they key building blocks of knowledge and understanding are embedded within the unit of project.

This is achieved by drawing together multiple other sources that we’ll share with the children to build the specific knowledge they will need.

Keeping Things Simple

Within this process, we’ll also be thinking about sequence – what comes first, what should come next - until we end up with a rough spine for our schemes of work.

This process is replicated across the curriculum – the nature of the sources change, but the thought process is the same.

In terms of making judgements, we keep things simple. We’re not interested in a detailed criteria-referenced model after all.

Instead we're looking for the two things I mentioned earlier:

-

-

- Has the pupil shown they can interpret what they’re looking at?

- Can they add to it with stuff they’ve got in their heads?

-

When the children complete their final source analysis (for most this will be a written analysis, but if writing is a barrier, we remove it by scribing for them, using assistive technology such as Clicker or finding another way to record their response), each teacher ranks (to themselves!) the work from strongest to weakest and identifies the piece of work that represents the cut-off or threshold point.

This is the child who has done just enough for us to say that they have analysed the source effectively.

In subjects like history, geography or art and design, this is entirely up to us as a school. There is no national expectation or exemplification in terms of what it should look like.

We simply need to decide on our expectations within our own setting.

To help with this, when we’ve ranked the work and identified the threshold point, we have a moderation staff meeting where we talk to year group partners and the year groups either side.

As a result of these conversations, there are often adjustments made to the threshold point and when we’re done, we’re able to place all the threshold pieces out from Y1 to Y6 to see what the progression looks like across school.

On Track. Or Not

Having established the cut-off in each class, the work is judged to be either pre or post threshold.

That is to say, the children are either on track with how well they are learning the curriculum in that subject, or they’re not.

This information is passed on to the next teacher during transition and will informs next steps.

If a child is judged not to be on track, we’ll dig a little deeper into their assessment piece to find out what went wrong.

It could be that they mis-interpreted the source they were presented with (sometimes, the children will share some knowledge they have but it bears little connection to the source they’re looking at). Other times, it’s clear that they just weren’t able to recall enough knowledge in order to do a good job.

This is valuable information for the next teacher – if a child lacked the knowledge required to be post threshold, then we don’t backtrack and attempt to fill in gaps – we just behave differently moving forward.

We might put additional strategies in place to help the child retain the knowledge from their new topic – it might be key vocabulary mats, knowledge organisers or increased repetition through retrieval practice.

If they lacked the procedural ability to analyse the source, this can be taken care of with increased scaffolding of the process.

Ultimately, as with any effective assessment, it is there to support the learning. [ITL]

If you'd like to know more about Jonathan's whole-school approaches to assessment across the curriculum, he'll be running another webinar on the topic on June 20th 2024.

Sign up details are here.

Check out his most recent blog on getting assessment right where he shares his strategies for source analysis.

And to find out more about his whole-school curriculum-wide approaches to primary teaching and learning check out his latest book, The Monkey-Proof Box, published by the Independent Thinking Press.

To find out more about booking Jonathan Lear for your school, college or organisation call us on 01267 211432 or drop us an email on learn@independentthinking.co.uk.

Enjoy a free no-obligation chat.

Make a booking. Haggle a bit.

Call us on +44 (0)1267 211432 or drop us a line at learn@independentthinking.co.uk.

About the author

Jonathan Lear

Jonathan Lear is a highly skilled and experienced teacher and deputy head in an inner-city primary school who is rewriting the rules when it comes to curriculum design and delivery. He is the author of Guerrilla Teaching and the Monkey-Proof Box.